Early Roman Empire Art Architecture Literature Society and Economy

Wall painting (1st century AD) from Pompeii depicting a multigenerational feast

The culture of ancient Rome existed throughout the about 1200-twelvemonth history of the civilization of Ancient Rome. The term refers to the culture of the Roman Republic, later on the Roman Empire, which at its peak covered an area from nowadays-day Lowland Scotland and Kingdom of morocco to the Euphrates.

Life in ancient Rome revolved around the city of Rome, its famed seven hills, and its awe-inspiring architecture such as the Colosseum, Trajan's Forum, and the Pantheon. The urban center likewise had several theaters and gymnasia, along with many taverns, baths and brothels. Throughout the territory under ancient Rome's command, residential architecture ranged from very modest houses to country villas, and in the capital city of Rome, there were imperial residences on the elegant Palatine Hill, from which the give-and-take palace is derived. The vast bulk of the population lived in the city center, packed into insulae (apartment blocks).

The city of Rome was the largest megalopolis of that time, with a population that may well have exceeded ane million people, with a high-cease estimate of iii.vi 1000000 and a depression-stop guess of 450,000. A substantial proportion of the population under the urban center's jurisdiction lived in innumerable urban centers, with population of at to the lowest degree 10,000 and several military settlements, a very high rate of urbanization past pre-industrial standards. The most urbanized part of the Empire was Italy, which had an estimated charge per unit of urbanization of 32%, the aforementioned charge per unit of urbanization of England in 1800. Most Roman towns and cities had a forum, temples and the aforementioned blazon of buildings, on a smaller scale, as establish in Rome. The large urban population required an enormous supply of food, which was a complex logistical task, including acquiring, transporting, storing and distribution of food for Rome and other urban centers. Italian farms supplied vegetables and fruits, but fish and meat were luxuries. Aqueducts were congenital to bring water to urban centers and wine and oil were imported from Hispania, Gaul and Africa.

In that location was a very large amount of commerce betwixt the provinces of the Roman Empire, since its roads and transportation engineering science were very efficient. The average costs of ship and the technology were comparable with 18th-century Europe. The later metropolis of Rome did not fill the space within its ancient Aurelian Walls until later 1870.

The bulk of the population nether the jurisdiction of ancient Rome lived in the countryside in settlements with less than 10,000 inhabitants. Landlords generally resided in cities and their estates were left in the care of farm managers. The plight of rural slaves was mostly worse than their counterparts working in urban aloof households. To stimulate a college labor productivity most landlords freed a large number of slaves and many received wages, but in some rural areas poverty and overcrowding were extreme.[1] Rural poverty stimulated the migration of population to urban centers until the early 2d century when the urban population stopped growing and started to decline.

Starting in the eye of the 2nd century BC, private Greek culture was increasingly in ascendancy, in spite of tirades against the "softening" effects of Hellenized culture from the conservative moralists. By the fourth dimension of Augustus, cultured Greek household slaves taught the Roman young (sometimes fifty-fifty the girls); chefs, decorators, secretaries, doctors, and hairdressers all came from the Greek East. Greek sculptures adorned Hellenistic mural gardening on the Palatine or in the villas, or were imitated in Roman sculpture yards past Greek slaves.

Against this human being background, both the urban and rural setting, one of history'southward most influential civilizations took shape, leaving behind a cultural legacy that survives in role today.

The Roman Empire began when Augustus became the first emperor of Rome in 31 BC and ended in the w when the last Roman emperor, Romulus Augustulus, was deposed by Odoacer in 476 Advertising. The Roman Empire, at its height (c. 117 Advert), was the nigh extensive political and social construction in Western culture. By 285 AD, the Empire had grown as well vast to be ruled from the central regime at Rome and and then was divided by Emperor Diocletian into a Western and an Eastern Roman Empire. In the east, the Empire continued every bit the Byzantine Empire until the death of Constantine Xi and the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Empire in 1453 Advertizement. The influence of the Roman Empire on Western culture was profound in its lasting contributions to about every aspect of Western culture.

[edit]

A late Republican banquet scene in a fresco from Herculaneum, Italy, c. fifty BC; the woman wears a transparent silk gown while the man to the left raises a rhyton drinking vessel

The center of the early social construction, dating from the fourth dimension of the agronomical tribal city state, was the family, which was not but marked by biological relations merely also by the legally constructed relation of patria potestas ("power of a father"). The pater familias was the absolute head of the family; he was the master over his married woman (if she was given to him cum manu, otherwise the father of the wife retained patria potestas), his children, the wives of his sons (again if married cum manu which became rarer towards the end of the Democracy), the nephews, the slaves and the freedmen (liberated slaves, the start generation yet legally inferior to the freeborn), disposing of them and of their appurtenances at will, even having them put to decease.

Slavery and slaves were function of the social order. The slaves were mostly prisoners of state of war. There were slave markets where they could be bought and sold. Roman law was not consistent about the status of slaves, except that they were considered like whatsoever other moveable holding. Many slaves were freed by the masters for fine services rendered; some slaves could relieve coin to buy their liberty. By and large, mutilation and murder of slaves was prohibited past legislation,[ citation needed ] although outrageous cruelty continued. In AD 4, the Lex Aelia Sentia specified minimum historic period limits for both owners (xx) and slaves (30) before formal manumission could occur.[2]

Apart from these families (chosen gentes) and the slaves (legally objects, mancipia, i.due east., "kept in the [master's] hand") there were plebeians that did non exist from a legal perspective. They had no legal capacity and were not able to make contracts, even though they were not slaves. To deal with this trouble, the so-called clientela was created. Past this establishment, a plebeian joined the family of a patrician (in a legal sense) and could shut contracts by mediation of his patrician pater familias. Everything the plebeian possessed or acquired legally belonged to the gens. He was not allowed to form his ain gens.

The authority of the pater familias was unlimited, be it in ceremonious rights every bit well as in criminal law. The rex's duty was to be head over the military, to deal with foreign politics and also to decide on controversies betwixt the gentes. The patricians were divided into three tribes (Ramnenses, Titientes, Luceres).

During the fourth dimension of the Roman Republic (founded in 509 BC) Roman citizens were allowed to vote. This included patricians and plebeians. Women, slaves, and children were not allowed to vote.

There were two assemblies: the comitia centuriata and the comitia populi tributa, which were fabricated up of all the citizens of Rome. In the comitia centuriata the Romans were divided according to age, wealth and residence. The citizens in each tribe were divided into five classes based on property and then each group was subdivided into two centuries by age. All in all, there were 373 centuries. Like the associates of tribes, each century had 1 vote. The comitia centuriata elected the praetors (judicial magistrates), the censors, and the consuls. The comitia tributa comprised xxx-5 tribes from Rome and the country. Each tribe had a single vote. The comitia tributa elected the quaestors (financial magistrates) and the patrician curule aedile.

Over time, Roman law evolved considerably, besides every bit social views, emancipating (to increasing degrees) family members. Justice profoundly increased, besides. The Romans became more efficient at considering laws and punishments.

Life in the ancient Roman cities revolved effectually the Forum, the central business district, where nearly of the Romans would go for marketing, shopping, trading, cyberbanking, and for participating in festivities and ceremonies. The Forum was also a place where orators would express themselves to mould public stance, and elicit support for any particular issue of interest to them or others. Before sunrise, children would go to schools or tutoring them at home would commence. Elders would wearing apparel, have a breakfast by 11 o'clock, have a nap and in the afternoon or evening would generally become to the Forum. Going to a public bathroom at to the lowest degree once daily was a habit with most Roman citizens. There were separate baths for men and women. The main difference was that the women's baths were smaller than the men's, and did not accept a frigidarium (common cold room) or a palaestra (do area).[ citation needed ]

Different types of outdoor and indoor entertainment, complimentary of price, were bachelor in ancient Rome. Depending on the nature of the events, they were scheduled during daytime, afternoons, evenings, or late nights. Huge crowds gathered at the Colosseum to watch events such as events involving gladiators, combats betwixt men, or fights between men and wild animals. The Circus Maximus was used for chariot racing.

Life in the countryside was slow-paced but lively, with numerous local festivals and social events. Farms were run by the farm managers, but estate owners would sometimes take a retreat to the countryside for residual, enjoying the splendor of nature and the sunshine, including activities like line-fishing, hunting, and riding. On the other mitt, slave labor slogged on continuously, for long hours and all seven days, and ensuring comforts and creating wealth for their masters. The average subcontract owners were amend off, spending evenings in economic and social interactions at the village markets. The day ended with a repast, generally left over from the noontime preparations.

Wear [edit]

Toga-clad statue, restored with the caput of the emperor Nerva

In aboriginal Rome, the cloth and the dress distinguished ane class of people from the other class. The tunic worn by plebeians (common people) like shepherds was made from coarse and dark cloth, whereas the tunic worn by patricians was of linen or white wool. A magistrate would wear the tunica angusticlavi; senators wore tunics with regal stripes (clavi), called tunica laticlavi. Armed forces tunics were shorter than the ones worn past civilians.

The many types of togas were also named. Boys, upwards until the festival of Liberalia, wore the toga praetexta, which was a toga with a ruddy or regal border, as well worn by magistrates in office. The toga virilis, (or toga pura) or man's toga was worn past men who had come of age to signify their citizenship in Rome. The toga picta was worn by triumphant generals and had embroidery of their skill on the battlefield. The toga pulla was worn in mourning.

Even footwear indicated a person'due south social status. Patricians wore red and orangish sandals, senators had brown footwear, consuls had white shoes, and soldiers wore heavy boots. Women wore closed shoes of colors such as white, yellow, or greenish.

The bulla was a locket-similar amulet worn by children. When well-nigh to marry, the adult female would donate her lunula to the household gods, along with her toys, to signify maturity and womanhood.

Men typically wore a toga, and women wore a stola. The woman's stola was a dress worn over a tunic, and was normally brightly colored. A fibula (or brooch) would be used every bit ornamentation or to hold the stola in place. A palla, or shawl, was often worn with the stola.

Nutrient [edit]

Since the commencement of the Republic until 200 BC, ancient Romans had very simple food habits. Simple food was by and large consumed at around 11 o'clock, and consisted of breadstuff, salad, olives, cheese, fruits, nuts, and cold meat left over from the dinner the night before. Breakfast was called ientaculum, luncheon was prandium, and dinner was chosen cena. Appetizers were called gustatio, and dessert was called secunda mensa ("second tabular array"). Ordinarily, a nap or rest followed this.

The family unit ate together, sitting on stools effectually a tabular array Later on, a divide dining room with dining couches was designed, chosen a triclinium. Fingers were used to take foods which were prepared beforehand and brought to the diners. Spoons were used for soups.

Wine in Rome did non get common or mass-produced until around 250 BC. Information technology was more than commonly produced around the time of Cato the Elderberry, who mentions in his book De agri cultura that the vineyard was the well-nigh important aspect of a good subcontract.[3] Wine was considered a staple drinkable, consumed at all meals and occasions by all classes and was quite inexpensive; nevertheless, it was e'er mixed with h2o.[ citation needed ] This was the instance even during explicit evening drinking events (comissatio) where an important function of the festivity was choosing an arbiter bibendi ("gauge of drinking") who was, among other things, responsible for deciding the ratio of wine to water in the drinking wine. Wine to water ratios of i:two, 1:3, or 1:four were commonly used. Many types of drinks involving grapes and love were consumed every bit well. Mulsum was honeyed wine, mustum was grape juice, mulsa was honeyed water. The per-person-consumption of wine per twenty-four hours in the city of Rome has been estimated at 0.8 to 1.1 gallons for males, and about 0.5 gallons for females. Fifty-fifty the notoriously strict Cato the Elder recommended distributing a daily ration of low quality vino of more than than 0.five gallons among the slaves forced to work on farms.[ citation needed ]

Drinking not-watered wine on an empty stomach was regarded as boorish and a sure sign of alcoholism whose debilitating physical and psychological effects were already recognized in ancient Rome. An accurate accusation of beingness an alcoholic—in the gossip-crazy society of the urban center bound to come to low-cal and easily verified—was a favorite and damaging way to discredit political rivals employed past some of Rome's greatest orators like Cicero and Julius Caesar. Prominent Roman alcoholics include Mark Antony, Cicero's own son Marcus (Cicero Minor) and the emperor Tiberius whose soldiers gave him the unflattering nickname Biberius Caldius Mero (lit. "Drunkard of Pure Vino," Sueton Tib. 42,1). Cato the Younger was too known every bit a heavy drinker, frequently establish stumbling habitation disoriented and the worse for wear in the early hours of morning by beau citizens.

During the Royal period, staple nutrient of the lower course Romans (plebeians) was vegetable porridge and bread, and occasionally fish, meat, olives and fruits. Sometimes, subsidized or gratuitous foods were distributed in cities. The patrician'due south aristocracy had elaborate dinners, with parties and wines and a variety of comestibles. Sometimes, dancing girls would entertain the diners. Women and children ate separately, just in the later Empire period, with permissiveness creeping in, even decent women would attend such dinner parties.

Pedagogy [edit]

Schooling in a more than formal sense was begun around 200 BC. Education began at the age of effectually six, and in the adjacent half dozen to vii years, boys and girls were expected to learn the nuts of reading, writing and counting. Past the historic period of twelve, they would be learning Latin, Greek, grammar and literature, followed by preparation for public speaking. Oratory was an art to be practiced and learned and good orators commanded respect; becoming an effective orator was 1 of the objectives of didactics and learning. Poor children could not afford education. In some cases, services of gifted slaves were utilized for imparting education. School was mostly for boys, but some wealthy girls were tutored at home; even so, girls could still get to school sometimes.

Linguistic communication [edit]

The native language of the Romans was Latin, an Italic language of the Indo-European family unit. Several forms of Latin existed, and the linguistic communication evolved considerably over fourth dimension, eventually becoming the Romance languages spoken today.

Initially a highly inflectional and constructed linguistic communication, older forms of Latin rely lilliputian on word order, carrying pregnant through a system of affixes attached to word stems. Similar other Indo-European languages, Latin gradually became much more than analytic over fourth dimension and acquired conventionalized word orders as information technology lost more than and more of its example arrangement and associated inflections. Its alphabet, the Latin alphabet, is based on the One-time Italic alphabet, which is in turn derived from the Greek alphabet. The Latin alphabet is still used today to write most European and many other languages.

Most of the surviving Latin literature consists almost entirely of Classical Latin. In the eastern one-half of the Roman Empire, which became the Byzantine Empire, Greek was the main lingua franca as it had been since the time of Alexander the Great, while Latin was more often than not used by the Roman administration and military. Eventually Greek would supervene upon Latin as both the official written and speech of the Eastern Roman Empire, while the diverse dialects of Vulgar Latin used in the Western Roman Empire evolved into the modern Romance languages all the same used today.

The expansion of the Roman Empire spread Latin throughout Europe, and over time Vulgar Latin evolved and dialectized in different locations, gradually shifting into a number of singled-out Romance languages beginning in around the 9th century. Many of these languages, including French, Italian, Portuguese, Romanaian, and Castilian, flourished, the differences betwixt them growing greater over fourth dimension.

Although English is Germanic rather than Romanic in origin—Britannia was a Roman province, just the Roman presence in Great britain had finer disappeared by the time of the Anglo-Saxon invasions—English today borrows heavily from Latin and Latin-derived words. Old English language borrowings were relatively sparse and drew mainly from ecclesiastical usage afterward the Christianization of England. When William the Conquistador invaded England from Normandy in 1066, he brought with him a considerable number of retainers who spoke Anglo-Norman French, a Romance language derived from Latin. Anglo-Norman French remained the language of the English upper classes for centuries, and the number of Latinate words in English increased immensely through borrowing during this Middle English period. More than recently, during the Modern English menstruum, the revival of involvement in classical civilisation during the Renaissance led to a dandy deal of conscious adaptation of words from Classical Latin authors into English.

Although Latin is an extinct language with very few contemporary fluent speakers, it remains in use in many ways. In particular, Latin has survived through Ecclesiastical Latin, the traditional linguistic communication of the Roman Catholic Church and one of the official languages of the The holy see. Although distinct from both Classical and Vulgar Latin in a number of ways, Ecclesiastical Latin was more than stable than typical Medieval Latin. More Classical sensibilities eventually re-emerged in the Renaissance with Humanist Latin. Due to both the prevalence of Christianity and the enduring influence of the Roman civilization, Latin became western Europe's lingua franca, a language used to cross international borders, such as for bookish and diplomatic usage. A deep knowledge of classical Latin was a standard part of the educational curriculum in many western countries until well into the 20th century, and is still taught in many schools today. Although information technology was eventually supplanted in this respect by French in the 19th century and English language in the 20th, Latin continues to run across heavy use in religious, legal, and scientific terminology, and in academia in full general.

The arts [edit]

Literature [edit]

Roman literature was from its very inception influenced heavily by Greek authors. Some of the earliest works currently discovered are of historical epics telling the early military history of Rome. As the Roman Republic expanded, authors began to produce poetry, comedy, history, and tragedy.

Mosaic depicting a theatrical troupe preparing for a performance

The Greeks and Romans founded history, and had great influence on the way history is written today. Cato the Elder was a Roman senator, besides every bit the first human to write history in Latin. Although theoretically opposed to Greek influence, Cato the Elderberry wrote the first Greek inspired rhetorical textbook in Latin (91), and combined strains of Greek and Roman history into a method combining both.[4] Ane of Cato the Elder's great historical achievements was the Origines, which chronicles the story of Rome from Aeneas to his own twenty-four hours, only this document is now lost. In the second and early on first centuries BC an attempt was fabricated, led by Cato the Elder, to use the records and traditions that were preserved, in order to reconstruct the entire past of Rome. The historians engaged in this chore are oftentimes referred to every bit the "Annalists", implying that their writings more or less followed chronological gild.[4]

In 123 BC, an official effort was made to provide a record of the whole of Roman history. This work filled fourscore books and was known as the Annales maximi. The composition recorded the official events of the Land, such as elections and commands, borough, provincial and cult business, set out in formal arrangements yr by yr.[4] During the reign of the early emperors of Rome there was a aureate age of historical literature. Works such as the Histories of Tacitus, the Gallic Wars by Julius Caesar and History of Rome by Livy have been passed downward through generations. Unfortunately, in the example of Livy, much of the script has been lost and it is left with a few specific areas: the founding of the city, the war with Hannibal, and its aftermath.

In the ancient world, poetry usually played a far more than important part of daily life than it does today. In full general, educated Greeks and Romans thought of poetry as playing a much more fundamental function of life than in mod times. Initially in Rome poesy was not considered a suitable occupation for important citizens, but the attitude changed in the second and outset centuries BC.[5] In Rome poetry considerably preceded prose writing in date. Every bit Aristotle pointed out, poetry was the kickoff sort of literature to agitate people's interest in questions of style. The importance of poetry in the Roman Empire was then stiff that Quintilian, the greatest authorization on education, wanted secondary schools to focus on the reading and education of poetry, leaving prose writings to what would at present exist referred to every bit the university stage.[5] Virgil represents the height of Roman ballsy poetry. His Aeneid was produced at the request of Maecenas and tells the story of flying of Aeneas from Troy and his settlement of the city that would become Rome. Lucretius, in his On the Nature of Things, attempted to explicate scientific discipline in an ballsy verse form. Some of his scientific discipline seems remarkably modernistic, but other ideas, particularly his theory of light, are no longer accepted. Later Ovid produced his Metamorphoses, written in dactylic hexameter verse, the meter of ballsy, attempting a complete mythology from the cosmos of the globe to his ain time. He unifies his subject thing through the theme of metamorphosis. Information technology was noted in classical times that Ovid'south work lacked the gravitas possessed by traditional epic poetry.

Catullus and the associated group of Neoteric poets produced poetry post-obit the Alexandrian model, which experimented with poetic forms challenging tradition. Catullus was also the beginning Roman poet to produce dear poetry, seemingly autobiographical, which depicts an matter with a woman called Lesbia. Nether the reign of the Emperor Augustus, Horace continued the tradition of shorter poems, with his Odes and Epodes. Martial, writing under the Emperor Domitian, was a famed author of epigrams, poems which were often abusive and censured public figures.

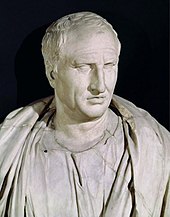

A bosom of Cicero, Capitoline Museums, Rome

Roman prose developed its sonority, dignity, and rhythm in persuasive speech communication.[6] Rhetoric had already been central to many great achievements in Athens, and then after studying the Greeks the Romans ranked oratory highly as a subject and a profession.[7] Written speeches were some of the first forms of prose writing in ancient Rome, and other forms of prose writing in the time to come were influenced by this. Sixteen books of Cicero's letters take survived, all published after Cicero's death past his secretary, Tito. The letters provide a expect at the social life in the days of the falling commonwealth, providing pictures of the personalities of this epoch.[viii] The letters of Cicero are vast and varied, and provide pictures of the personalities of this epoch. Cicero's personality is almost clearly revealed, emerging every bit a vain vacillating, snobbish man. Cicero'southward passion for the public life of the capital also emerges from his letters, nearly conspicuously when he was in exile and when he took on a provincial governorship in Asia Small-scale. The letters also contain much about Cicero'due south family life, and its political and financial complications.[8]

Roman philosophical treatises have had great influence on the globe, but the original thinking came from the Greeks. Roman philosophical writings are rooted in four 'schools' from the historic period of the Hellenistic Greeks.[9] The four 'schools' were that of the Epicureans, Stoics, Peripatetics, and Academy.[9] Epicureans believed in the guidance of the senses, and identified the supreme goal of life to be happiness, or the absence of pain. Stoicism was founded by Zeno of Citium, who taught that virtue was the supreme good, creating a new sense of ethical urgency. The Perpatetics were followers of Aristotle, guided by his science and philosophy. The Academy was founded by Plato and was based on the Sceptic Pyro's idea that real knowledge could be caused. The Academy also presented criticisms of the Gluttonous and Stoic schools of philosophy.[ten]

The genre of satire was traditionally regarded every bit a Roman innovation, and satires were written by, amid others, Juvenal and Persius. Some of the almost popular plays of the early on Commonwealth were comedies, especially those of Terence, a freed Roman slave captured during the Kickoff Punic State of war.

A great deal of the literary work produced past Roman authors in the early Republic was political or satirical in nature. The rhetorical works of Cicero, a self-distinguished linguist, translator, and philosopher, in particular, were popular. In addition, Cicero's personal letters are considered to be one of the best bodies of correspondence recorded in antiquity.

Visual fine art [edit]

Most early on Roman painting styles show Etruscan influences, particularly in the practise of political painting. In the 3rd century BC, Greek art taken as booty from wars became popular, and many Roman homes were decorated with landscapes by Greek artists. Evidence from the remains at Pompeii shows various influence from cultures spanning the Roman globe.

An early Roman way of note was "Incrustation", in which the interior walls of houses were painted to resemble colored marble. Some other style consisted of painting interiors as open landscapes, with highly detailed scenes of plants, animals, and buildings.

Portrait sculpture during the menstruation utilized youthful and classical proportions, evolving afterward into a mixture of realism and idealism. During the Antonine and Severan periods, more than ornate hair and bearding became prevalent, created with deeper cutting and drilling. Advancements were besides made in relief sculptures, usually depicting Roman victories.

Music [edit]

Music was a major part of everyday life in aboriginal Rome. Many individual and public events were accompanied by music, ranging from nightly dining to military machine parades and manoeuvres.

Some of the instruments used in Roman music are the tuba, cornu, aulos, askaules, flute, panpipes, lyre, lute, cithara, tympanum, drums, hydraulis and the sistrum.

Architecture [edit]

In its initial stages, the ancient Roman architecture reflected elements of architectural styles of the Etruscans and the Greeks. Over a period of time, the style was modified in tune with their urban requirements, and civil engineering and building construction applied science became adult and refined. The Roman concrete has remained a riddle,[11] and even after more than two thousand years some ancient Roman structures still stand magnificently, similar the Pantheon (with one of the largest unmarried bridge domes in the globe) located in the business district of today's Rome.

The architectural mode of the capital city of ancient Rome was emulated by other urban centers under Roman control and influence,[12] like the Verona Loonshit, Verona, Italy; Curvation of Hadrian, Athens, Hellenic republic; Temple of Hadrian, Ephesus, Turkey; a Theatre at Orange, French republic; and at several other locations, for example, Lepcis Magna, located in Libya.[thirteen] Roman cities were well planned, efficiently managed and neatly maintained. Palaces, private dwellings and villas, were elaborately designed and town planning was comprehensive with provisions for different activities by the urban resident population, and for countless migratory population of travelers, traders and visitors passing through their cities. Marcus Vitruvius Pollio, a 1st-century BC Roman architect's treatise De architectura, with various sections, dealing with urban planning, building materials, temple construction, public and individual buildings, and hydraulics, remained a classic text until the Renaissance.

Sports and entertainment [edit]

The ancient city of Rome had a place called the Campus, a sort of drill ground for Roman soldiers, which was located near the Tiber. Later, the Campus became Rome'southward runway and field playground, which fifty-fifty Julius Caesar and Augustus were said to have frequented. Imitating the Campus in Rome, similar grounds were developed in several other urban centers and military settlements.

In the Campus, the youth assembled to play, exercise, and indulge in appropriate sports, which included jumping, wrestling, boxing and racing. Riding, throwing, and swimming were likewise preferred physical activities. In the countryside, pastimes likewise included fishing and hunting. Females did not participate in these activities. Ball playing was a popular sport and ancient Romans had several ball games, which included handball (expulsim ludere), field hockey, grab, and some course of football.

Board games played in ancient Rome included dice (tesserae or tali), Roman chess (latrunculi), Roman checkers (Calculi), tic-tac-toe (terni lapilli), and ludus duodecim scriptorum and tabula, predecessors of backgammon.

There were several other activities to keep people engaged similar chariot racing, musical and theatrical performances, public executions and gladiatorial combat. In the Colosseum, Rome'southward amphitheatre, 60,000 persons could exist accommodated. There are too accounts of the Colosseum's flooring being flooded to concur mock naval battles for the public to watch.

In add-on to these, Romans too spent their share of time in bars and brothels, and graffiti[14] carved into the walls of these buildings was common. Based on the number of messages constitute on bars, brothels, and bathhouses, information technology's articulate that they were popular places of leisure and people spent a bargain of time there. The walls of the rooms in the lupanar, 1 of the only known remaining brothels in Pompeii, are covered in graffiti in a multitude of languages, showcasing how multicultural aboriginal Rome was.

Religion [edit]

The Romans thought of themselves equally highly religious,[15] and attributed their success as a world power to their commonage piety (pietas) in maintaining practiced relations with the Gods. According to legendary history, most of Rome's religious institutions could be traced to its founders, particularly Numa Pompilius, the Sabine 2d King of Rome, who negotiated directly with the Gods. This primitive religion was the foundation of the mos maiorum, "the mode of the ancestors" or simply "tradition," viewed every bit central to Roman identity.

The priesthoods of public faith were held by members of the aristocracy classes. There was no principle analogous to "separation of church and state" in ancient Rome. During the Roman Democracy (509–27 BC), the same men who were elected public officials served as augurs and pontiffs. Priests married, raised families, and led politically active lives. Julius Caesar became pontifex maximus before he was elected consul. The augurs read the will of the gods and supervised the marking of boundaries every bit a reflection of universal lodge, thus sanctioning Roman expansionism as a matter of divine destiny. The Roman triumph was at its core a religious procession in which the victorious general displayed his piety and his willingness to serve the public good by dedicating a portion of his spoils to the gods, especially Jupiter, who embodied just dominion. As a result of the Punic Wars (264–146 BC), when Rome struggled to establish itself as a ascendant power, many new temples were built past magistrates in fulfillment of a vow to a deity for assuring their military success.

Roman religion was thus mightily pragmatic and contractual, based on the principle of do ut des ("I requite that you might give"). Faith depended on noesis and the right do of prayer, ritual, and sacrifice, not on faith or dogma, although Latin literature preserves learned speculation on the nature of the divine and its relation to human affairs. Even the most skeptical among Rome's intellectual aristocracy such as Cicero, who was an diviner, saw religion equally a source of social guild.

For ordinary Romans, religion was a part of daily life.[16] Each dwelling had a household shrine at which prayers and libations to the family's domestic deities were offered. Neighborhood shrines and sacred places such as springs and groves dotted the city. The Roman calendar was structured around religious observances. In the Imperial Era, every bit many as 135 days of the year were devoted to religious festivals and games (ludi).[17] Women, slaves, and children all participated in a range of religious activities. Some public rituals could be conducted only by women, and women formed what is perhaps Rome'south nearly famous priesthood, the state-supported Vestal Virgins, who tended Rome'due south sacred hearth for centuries, until disbanded nether Christian domination.

The Romans are known for the slap-up number of deities they honored. The presence of Greeks on the Italian peninsula from the outset of the historical period influenced Roman culture, introducing some religious practices that became every bit cardinal every bit the cult of Apollo. The Romans looked for common footing between their major gods and those of the Greeks, adapting Greek myths and iconography for Latin literature and Roman fine art. Etruscan organized religion was also a major influence, particularly on the practice of augury, since Rome had once been ruled by Etruscan kings.

Mystery religions imported from the Near Due east (Ptolemaic Egypt, Persia and Mesopotamia), which offered initiates salvation through a personal God and eternal life later the decease, were a affair of personal selection for an individual, practiced in addition to conveying on 1'due south family rites and participating in public religion. The mysteries, however, involved exclusive oaths and secrecy, conditions that bourgeois Romans viewed with suspicion as feature of "magic," conspiracy (coniuratio), and destructive activity. Sporadic and sometimes vicious attempts were made to suppress religionists who seemed to threaten traditional Roman morality and unity, as with the Senate's efforts to restrict the Bacchanals in 186 BC.

Equally the Romans extended their dominance throughout the Mediterranean world, their policy in general was to absorb the deities and cults of other peoples rather than try to eradicate them,[xviii] since they believed that preserving tradition promoted social stability.[19]

I way that Rome incorporated diverse peoples was past supporting their religious heritage, building temples to local deities that framed their theology within the hierarchy of Roman religion. Inscriptions throughout the Empire record the side-by-side worship of local and Roman deities, including dedications made by Romans to local gods.[21] Past the height of the Empire, numerous international deities were cultivated at Rome and had been carried to even the most remote provinces (amid them Cybele, Isis, Osiris, Serapis, Epona), and Gods of solar monism such as Mithras and Sol Invictus, found equally far due north as Roman Uk. Because Romans had never been obligated to cultivate one deity or ane cult only, religious tolerance was not an effect in the sense that information technology is for competing monotheistic systems.[22] The monotheistic rigor of Judaism posed difficulties for Roman policy that led at times to compromise and the granting of special exemptions, merely sometimes to intractable conflict.

In the wake of the Republic'south plummet, State organized religion had adapted to support the new regime of the Emperors. Augustus, the showtime Roman emperor, justified the novelty of ane-human rule with a vast program of religious revivalism and reform. Public vows formerly made for the security of the Republic now were directed at the wellbeing of the Emperor. So-called "Emperor worship" expanded on a grand scale the traditional Roman veneration of the ancestral expressionless and of the Genius, the divine tutelary of every private. Purple cult became 1 of the major ways Rome advertised its presence in the provinces and cultivated shared cultural identity and loyalty throughout the Empire: rejection of the Land religion was tantamount to treason. This was the context for Rome'southward conflict with Christianity, which Romans variously regarded every bit a form of atheism and threat to the stability of the Empire,[23] causing the prosecution of anti-Christian policies; nether Emperor Trajan's reign (Advertising 98–117), Roman intellectuals and functionaries (Lucian of Samosata, Tacitus,[24] Suetonius,[24] Pliny the Younger,[24] and Celsus)[23] gained knowledge about the Jewish roots of Early Christians, therefore many of them considered Christianity to be some sort of superstitio Iudaica.[23] [24] [25]

From the 2nd century onward, the Church Fathers began to condemn the diverse religions practiced throughout the Empire collectively as "Pagan."[26] In the early on fourth century, Constantine the Great and his half-brother Licinius stipulated an understanding known as the Edict of Milan (313), which granted freedom to all religions to exist freely practiced in the Roman Empire; following the Edict's declaration, the conflict between the two Emperors exacerbated, ending with the execution of both Licinius and the co-Emperor Sextus Martinianus equally ordered past Constantine after Licinius' defeat in the Battle of Chrysopolis (324).

Head of Constantine the Great, part of a colossal statue. Bronze, 4th century, Musei Capitolini, Rome.

Constantine ruled the Roman Empire as sole emperor for the remainder of his reign. Some scholars allege that his main objective was to proceeds unanimous approval and submission to his potency from all classes, and therefore chose Christianity to conduct his political propaganda, assertive that it was the most appropriate organized religion that could fit with the Royal cult (run into besides Sol Invictus). Regardless, under Constantine's rule Christianity expanded throughout the Empire, launching the era of Christian Church's dominance under the Constantinian dynasty.[27]

Still, if Constantine himself sincerely converted to Christian organized religion or remained loyal to Paganism is nonetheless a thing of debate between scholars (see also Constantine'due south Religious policy).[28] His formal conversion to Christianity in 312 is almost universally best-selling among historians,[27] [29] despite that he was baptized only on his deathbed past the Arian bishop Eusebius of Nicomedia (337);[30] the real reasons behind it remain unknown and are debated too.[28] [29] According to Hans Pohlsander, Professor Emeritus of History at the Academy at Albany, SUNY, Constantine'south conversion was just another instrument of Realpolitik in his easily meant to serve his political interest in keeping the Empire united under his control:

The prevailing spirit of Constantine's government was one of conservatorism. His conversion to and support of Christianity produced fewer innovations than one might have expected; indeed they served an entirely conservative cease, the preservation and continuation of the Empire.

—Hans Pohlsander, The Emperor Constantine [31]

The Emperor and Neoplatonic philosopher Julian the Apostate made a short-lived attempt to restore traditional religion and Paganism, and to reaffirm the special status of Judaism, but in 391, under Theodosius I, Nicene Christianity became the official State church of the Roman Empire to the exclusion of all other Christian churches and Hellenistic religions, including Roman organized religion itself. Pleas for religious tolerance from traditionalists such as the senator Symmachus (d. 402) were rejected, and Christian monotheism became a feature of Imperial domination. Heretics as well equally non-Christians were subject area to exclusion from public life or persecution, but, despite the decline of Greco-Roman polytheism, Rome's original religious bureaucracy and many aspects of its ritual influenced Christian religion as a whole;[32] various pre-Christian beliefs and practices survived also in Christian festivals and local traditions.

Philosophy [edit]

Ancient Roman philosophy was heavily influenced by the ancient Greeks and the schools of Hellenistic philosophy; notwithstanding, unique developments in philosophical schools of thought occurred during the Roman period every bit well. Interest in philosophy was first excited at Rome in 155 BC. past an Athenian embassy consisting of the Academic Skeptic Carneades, the Stoic Diogenes, and the Peripatetic Critolaus.[33]

During this time Athens declined as an intellectual center of thought while new sites such as Alexandria and Rome hosted a variety of philosophical discussion.[34]

Science [edit]

| | This department is empty. You can help by adding to it. (Dec 2020) |

See likewise [edit]

- Classical antiquity

- Gallo-Roman culture

- Roman United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland

- Romanization

- Romanization of Hispania

- Theatre of ancient Rome

- Romanization of Anatolia

References [edit]

- ^ For example, a Romano-Egyptian text attests to the sharing of ane small farmhouse past 42 people; elsewhere, vi families held common involvement in a single olive tree. See Alfoldy, Geza., The Social History of Rome (Routledge Revivals) 2014 (online e-edition, unpaginated: accessed October 11th, 2016)

- ^ Gardner, Jane (1991). "The Purpose of the Lex Fufia Caninia". Echos du Monde Classique: Classical Views. 35, 1: 21–39 – via Project MUSE.

- ^ Eastward. M. Jellinek, Drinkers and Alcoholics in Ancient Rome.

- ^ a b c Grant, Michael (1954). Roman Literature. Cambridge England: University Press. pp. 91–94.

- ^ a b Grant, Michael (1954). Roman Literature. Cambridge England: University Press. p. 134.

- ^ Tenney, Frank (1930). Life and Literature in the Roman Republic. Berkeley California: University of California Press. p. 132.

- ^ Tenney, Frank (1930). Life and Literature in the Roman Republic. Berkeley California: University of California Printing. p. 35.

- ^ a b Grant, Michael (1954). Roman Literature. Cambridge England: Academy Press. pp. 78–84.

- ^ a b Grant, Michael (1954). Roman Literature. Cambridge England: University Press. pp. 30–45.

- ^ Grant, Michael (1954). Roman Literature. Cambridge England: University Press. pp. Notes.

- ^ The Riddle of Ancient Roman Concrete, Past David Moore, P.E., 1995, Retired Professional Engineer, Bureau of Reclamation (This article outset appeared in "The Spillway" a newsletter of the US Dept. of the Interior, Bureau of Reclamation, Upper Colorado Region, Feb, 1993)

- ^ "Roman Art and Architecture". UCCS.edu. Archived from the original on September 8, 2006. Retrieved July 14, 2013.

- ^ Lepcis Magna - Window on the Roman World in North Africa

- ^ Harvey, Brian. "Graffiti from Pompeii". Graffiti from Pompeii. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved February 23, 2016.

- ^ Ehlke, Troy D. (2008-10-16). Crossroads of Agony: Suffering and Violence in the Christian Tradition. Xlibris Corporation. ISBN978-i-4691-0298-6.

- ^ Jörg Rüpke, "Roman Faith – Religions of Rome," in A Companion to Roman Religion (Blackwell, 2007), p. four.

- ^ Matthew Bunson, A Lexicon of the Roman Empire (Oxford University Press, 1995), p. 246.

- ^ "This mentality," notes John T. Koch, "lay at the core of the genius of cultural assimilation which made the Roman Empire possible"; entry on "Interpretatio romana," in Celtic Civilization: A Historical Encyclopedia (ABC-Clio, 2006), p. 974.

- ^ Rüpke, "Roman Religion – Religions of Rome," p. 4; Benjamin H. Isaac, The Invention of Racism in Classical Antiquity (Princeton Academy Printing, 2004, 2006), p. 449; Westward.H.C. Frend, Martyrdom and Persecution in the Early on Church: A Study of Disharmonize from the Maccabees to Donatus (Doubleday, 1967), p. 106.

- ^ Chiliad. W. Bromiley (ed.), The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, Vol. 4 (Eerdmans, 1988), p. 116. ISBN 0-8028-3784-0.

- ^ Janet Huskinson, Experiencing Rome: Culture, Identity and Power in the Roman Empire (Routledge, 2000), p. 261.

- ^ A classic essay on this topic is Arnaldo Momigliano, "The Disadvantages of Monotheism for a Universal Country," in Classical Philology, 81.4 (1986), pp. 285–297.

- ^ a b c Michael Frede, "Origen's Treatise Confronting Celsus," in M. Edwards, M. Goodman, S. Toll and C. Rowland (ed.), Apologetics in the Roman Empire: Pagans, Jews, and Christians (Oxford Academy Printing, 2002), pp. 133-134. ISBN 0-19-826986-ii; Antonia Tripolitis, Religions of the Hellenistic-Roman Age (Eerdmans, 2001), pp. 99-101. ISBN 978-0-8028-4913-7.

- ^ a b c d R. 50. Wilken, The Christians as the Romans Saw Them (Yale University Press, 2003), pp. 32-fifty. ISBN 978-03-00-09839-6.

- ^ For the Roman sources on early Christianity, see also Pliny the Younger on Christians, Suetonius on Christians, and Tacitus on Christ.

- ^ See Peter Dark-brown in 1000. Due west. Bowersock, P. Brown and O. Grabar (ed.); Belatedly Artifact: A Guide to the Postclassical World (Harvard University Printing, 1999), pp. 625-626, for the epithet "Infidel" used every bit a marking of socio-religious inferiority in Latin Christian polemic and apologetics.

- ^ a b Wendy Doniger (ed.), "Constantine I," in Britannica Encyclopedia of Globe Religions (Encyclopædia Britannica, 2006), p. 262.

- ^ a b Noel Lenski (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to the Historic period of Constantine (Cambridge University Press, 2006), "Introduction". ISBN 978-0-521-81838-4.

- ^ a b A. H. M. Jones, Constantine and the Conversion of Europe (University of Toronto Printing, 2003), p. 73. ISBN 0-8020-6369-ane.

- ^ Hans A. Pohlsander, The Emperor Constantine (Routledge, NY 2004), pp. 82–84. ISBN 0-415-31938-ii; Lenski, "Reign of Constantine" (The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Constantine), p. 82.

- ^ Pohlsander, The Emperor Constantine, pp. 78–79.

- ^ Stefan Heid, "The Romanness of Roman Christianity," in A Companion to Roman Organized religion (Blackwell, 2007), pp. 406–426; on vocabulary in item, Robert Schilling, "The Refuse and Survival of Roman Faith," in Roman and European Mythologies (University of Chicago Printing, 1992, from the French edition of 1981), p. 110.

- ^ "Roman Philosophy | Net Encyclopedia of Philosophy".

- ^ Annas, Julia. (2000). Voices of Ancient Philosophy : an Introductory Reader. Oxford Academy Printing. ISBN978-0-19-512694-v. OCLC 870243656.

Bibliography [edit]

- Elizabeth South. Cohen, Laurels and Gender in the Streets of Early Modern Rome, The Journal of Interdisciplinary History, Vol. 22, No. 4 (Spring, 1992), pp. 597-625

- Edward Gibbon, The Refuse and Fall of the Roman Empire

- Tom Holland, The Concluding Years of the Roman Republic ISBN 0-385-50313-X

- Ramsay MacMullen, 2000. Romanization in the Time of Augustus (Yale University Printing)

- Paul Veyne, editor, 1992. A History of Individual Life: I From Pagan Rome to Byzantium (Belknap Printing of Harvard University Press)

- Karl Wilhelm Weeber, 2008. Nachtleben im Alten Rom (Primusverlag)

- Karl Wilhelm Weeber, 2005. Dice Weinkultur der Römer

- J.H. D'Arms, 1995. Heavy drinking and drunkenness in the Roman world, in O.Murray In Vino Veritas

External links [edit]

- An interactive Roman map

- Rome Reborn − A Video Bout through Ancient Rome based on a digital model

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Culture_of_ancient_Rome

0 Response to "Early Roman Empire Art Architecture Literature Society and Economy"

Post a Comment